Beginning in the sixteenth century, successive waves of Europeans—the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and British—sought to dominate the spice trade at its sources in IndiaSpice Islands' (Maluku) of Indonesia. This meant finding a way to Asia to cut out Muslim merchants who, with their Venetian outlet in the Mediterranean, monopolised spice imports to Europe. Astronomically priced at the time, spices were highly coveted not only to preserve and make poorly preserved meat palatable, but also as medicines and magic potions. and the '

The arrival of Europeans in South East Asia is often regarded as the watershed moment in its history. Other scholars consider this view untenable,[17] arguing that European influence during the times of the early arrivals of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was limited in both area and depth. This is in part due to Europe not being the most advanced or dynamic area of the world in the early fifteenth century. Rather, the major expansionist force of this time was Islam; in 1453, for example, the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople, while Islam continued to spread through Indonesia and the Philippines. European influence, particularly that of the Dutch, would not have its greatest impact on Indonesia until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Portuguese

Europeans were, however, making technological advances. New found Portuguese expertise in navigation, ship building and weaponry allowed them to make daring expeditions of exploration and expansion. Starting with the first exploratory expeditions sent from newly-conquered Malacca in 1512, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in Indonesia, and sought to dominate the sources of valuable spices[18] and to extend the Catholic church's missionary efforts. Initial Portuguese attempts to establish a coalition and peace treaty in 1512 with the Sunda Kingdom at Kalapa [19] failed due to hostilities amongst other indigenous Javan kingdoms. The Portuguese turned east to Maluku, which comprised a varied collection of principalities and kingdoms that were occasionally at war with each other but maintained significant inter-island and international trade. Through both military conquest and alliance with local rulers, they established trading posts, forts, and missions in eastern Indonesia including the islands of Ternate, Ambon, and Solor. The height of Portuguese missionary activities, however, came at the latter half of the sixteenth century, after the pace of their military conquest in the archipelago had stopped and their commercial interest in Indonesia was shifting to Japan, Macau and China as well as sugar in Brazil and the Atlantic slave trade.

The Portuguese presence in Indonesia was reduced to Solor, Flores and Timor in modern day Nusa Tenggara, following defeat in 1575 at Ternate at the hands of indigenous Ternateans, Dutch conquests in Ambon, north Maluku and Banda, and a general failure to maintain control of trade in the region.[20] In comparison with the original Portuguese ambition to dominate Asian trade, their influences on Indonesian culture are small: the romantic keroncong guitar ballads; a number of Indonesian words which reflect Portuguese’s role as the 'lingua franca' of the archipelago alongside Malay; and many family names in eastern Indonesia such as da Costa, Dias, de Fretes, Gonsalves, etc. The most significant impacts of the Portuguese arrival were the disruption and disorganisation of the trade network mostly as a result of their conquest of Malacca, and the first significant plantings of Christianity in Indonesia. There have continued to be Christian communities in eastern Indonesia through to the present, which has contributed to a sense of shared interest with Europeans, particularly among the Ambonese.[21]

Dutch East-India Company

In 1602, the Dutch parliament awarded the VOC a monopoly on trade and colonial activities in the region at a time before the company controlled any territory in Java. In 1619, the VOC conquered the West Javan city of Jayakarta, where they founded the city of Batavia (present-day Jakarta). The VOC became deeply involved in the internal politics of Java in this period, and fought in a number of wars involving the leaders of Mataram and Banten (Bantam).

The Dutch followed the Portuguese aspirations, courage, brutality and strategies but brought better organisation, weapons, ships, and superior financial backing. Although they failed to gain complete control of the Indonesian spice trade, they had much more success than the previous Portuguese efforts. They exploited the factionalisation of the small kingdoms in Java that had replaced Majapahit, establishing a permanent foothold in Java, from which grew a land-based colonial empire which became one of the world's richest colonial possessions.[22]

Dutch state rule

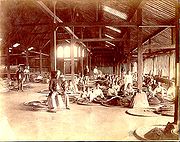

After the VOC was dissolved in 1800 following bankruptcy,[18] and after a short British rule under Thomas Stamford Raffles, the Dutch state took over the VOC possessions in 1816. A Javanese uprising was crushed in the Java War of 1825-1830. After 1830 a system of forced cultivations and indentured labour was introduced on Java, the Cultivation System (in Dutch: cultuurstelsel). This system brought the Dutch and their Indonesian collaborators enormous wealth. The cultivation system tied peasants to their land, forcing them to work in government-owned plantations for 60 days of the year. The system was abolished in a more liberal period after 1870. In 1901 the Dutch adopted what they called the Ethical Policy, which included somewhat increased investment in indigenous education, and modest political reforms.

For most of the colonial period, Dutch control over its territories in the Indonesian archipelago was tenuous. It was only in the early 20th century, three centuries after the first Dutch trading post, that the full extent of the colonial territory was established and direct colonial rule exerted across what would become the boundaries of the modern Indonesian state.[23] Portuguese Timor, now East Timor, remained under Portuguese rule until 1975 when it was invaded by Indonesia. The Indonesian government declared the territory an Indonesian province but relinquished it in 1999.